- Home

- Ellen Conford

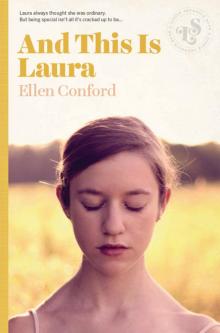

And This Is Laura

And This Is Laura Read online

And This Is Laura

Copyright © 1977 by Ellen Conford.

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission of the publisher.

Please direct inquiries to:

Lizzie Skurnick Books

an imprint of Ig Publishing

392 Clinton Avenue #1S

Brooklyn, NY 11238

www.igpub.com

ISBN: 978-1-939601-23-0

And This Is Laura

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

1

I’LL BET NONE of this would have happened if I hadn’t been such an ordinary, run-of-the-mill person. If I’d been my sister, Jill, for instance, I’d have been too busy rehearsing Romeo and Juliet and winning bowling trophies; if I’d been my brother Douglas, my time would have been occupied with piano playing and captaining the Hillside High School debating team. Even my little brother, Dennis, is so busy memorizing TV commercials and doing his daily counting he hardly has time left for anything else.

Dennis is counting to a million. Why? I have no idea. Why do people climb mountains?

For a long time I was convinced I was adopted; how else could you explain the fact that while surrounded by a family of overachievers, there was absolutely nothing that I was brilliant at? Oh, I do well enough in school. Very well, in fact. Like almost straight “A’s.” But I don’t do anything special. I mean, if my mother were introducing us she could say, “My daughter Jill, the actress. My son Douglas, the musician. My son Dennis; would you like to hear him do the Anacin commercial?”

But when she got around to me, what could she say? “And this is Laura. She’s twelve.”

Of course she wouldn’t. She never has. She’s a little casual about introductions anyway. She’s a little casual about everything. What she usually says is “Meet the mob.”

Nevertheless, being utterly average in my family is a tough row to hoe, believe me.

And it’s not merely the lack of my outstanding ability that sets me apart. It is, in fact, a whole question of life-style.

Take breakfast, for instance.

Now, my idea of breakfast is: orange juice, scrambled eggs or cereal, toast and milk. A nice, normal, healthy breakfast, right?

For Dennis’s breakfast, my mother plops fourteen different little packets of dry cereal on the table, each one of them coated with sugar, and lets Dennis eat whichever ones he wants. And he sits there wolfing down Sugar Stinkies and Cocoa Barfos and Hunny-Bunnies until I can practically hear his teeth disintegrating.

And when I point out that he’s ruining his entire mouth with that junk, you know what she says? “He gets fluoride treatments.”

Jill’s breakfast consists of a stalk of celery, two tablespoons of wheat germ and black coffee. Black coffee! I mean, she’s fifteen years old.

“Don’t you realize she’s going to stunt her growth with that?” I ask.

And my father says, “She’s five foot six. How much growth can she stunt?”

Douglas eats frozen pizza for breakfast. That is, he doesn’t eat it frozen—my mother sticks a couple of those packaged pizzas in the oven and heats them up. At least he has milk with them. My mother says pizza is a perfectly fine breakfast nutritionally because the cheese has protein and calcium and the dough is like toast or bread and the tomato sauce has Vitamin C, like orange juice. Okay. She’s got me there. But it’s not normal.

My father has been known to eat veal kidneys. He points out that in places like England kidneys are very commonly eaten at breakfast. But we are not living in England. We are living here and kidneys are not commonly eaten for breakfast in the United States. And the smell of kidneys cooking at seven o’clock in the morning . . .

Even Jill has threatened to report him to the Environmental Protection Agency for fouling up the air, but he just says, “Stop picking on my kidneys.”

My mother doesn’t eat breakfast. She drinks coffee. I don’t blame her. Sometimes when I look around at what the rest of the family is eating I lose my appetite too. But back in the first grade I learned that A Good Breakfast Is The Start Of A Good Day, so I force myself.

Now, this whole story has to begin somewhere (and it’s about time, too) so since I’ve begun to fill you in on the hideous details of breakfast, we might as well start there.

It is a drizzly morning in late September as we look in on the Hoffman household. A typical Monday at 522 Woodbine Way, with nothing to distinguish it from any other Monday. As we join the Hoffmans, we hear Laura say . . .

“But that’s not logical. If you’re so concerned with our individual likes and dislikes at breakfast, how come we all have to eat the same thing for dinner?”

“Because preparing dinner is more trouble than preparing breakfast. Therefore, preparing six dinners would be six times more difficult than preparing five breakfasts.”

“That’s logical,” my father said.

“And besides,” my mother went on, “anyone who doesn’t like what we have for dinner is always free to go and cook whatever he or she prefers.”

“What’s the matter, Joe? You’re so grumpy today. Frankly, Bill, this irregularity is getting me down. I’ve tried everything—”

“Dennis, please. Not first thing in the morning.” Jill held her hand to her head.

“Nagging headache? Why suffer? For fast, fast, fast relief—”

“DENNIS!”

“Douglas, dear, I think your pizza is burning.”

He didn’t look up from his newspaper. “ ’S all right. I like it that way.”

“It’s not enough,” I said irritably, “that he has to eat pizza for breakfast—it’s got to be burnt pizza.”

Douglas sighed and plopped his paper down on the table. “All right, all right, Fussbudget. I’ll take it out so it doesn’t offend your delicate sense of smell.”

“Don’t do it on my account,” I snapped. “I was just worried about your being able to read the paper through all that black smoke.”

“You’re exaggerating slightly.” He snatched the pizzas out of the oven and dropped them onto a plate. “As usual.”

Douglas is sixteen. He’s extremely sarcastic. I don’t exaggerate. I report everything exactly as it happens.

“The first meeting of the dramatics club is this afternoon,” I said, “so I’ll be a little late.”

No one was very impressed. Why should they be? Jill has had the lead in every play she’s been in since elementary school. The last play I was in was a second-grade production about the Basic Food Groups called something like “Mealtime Frolics of 1970.” I played a grape. Along with thirteen other grapes I made up a bunch.

“You’ll enjoy it,” Jill said. “Is Mr. Kane still the advisor? He was really nice.”

“Sure. He’s my English teacher, remember? He asked me if I was going to join. He said, ‘Your sister was so talented.’ ”

“He remembers me? Isn’t that nice?”

That, I thought, depends on your point of view.

“What has that got to do with your joining the club?” my father asked.

I shrugged. “I don’t know. I guess he thinks it runs in the family.”

“Ridiculous,” he scoffed. “You’re an individual.”

“And individual people,” Dennis droned, “have individual hair problems. Don’t settle for just any shampoo. Hi-Lite makes a shampoo that’s just right

for your particular hair problem. Cucumber for oily hair, strawberry creme for dry hair and Hi-Protein Egg for normal hair. Do you think my voice is getting any deeper?”

“Noticeably,” my father said. Dennis is seven. He wants to be a TV announcer when he grows up.

Douglas folded up the paper and pushed his chair back. “Better get going. Coming, Bernhardt?”

Jill gulped down the last of her black coffee and jumped up.

“ ’Bye, all.”

“ ’Bye, all,” Douglas simpered and waggled his fingers at us. Jill whacked him on the shoulder.

I finished my eggs and cocoa and reminded Dennis that if he dawdled much longer he’d be late for school.

“Don’t worry, Laura,” my mother said, with a look of amusement. “I’ll make sure he’s not late.”

“Okay, okay,” I said hastily. “I was just trying to be helpful.” Actually, I had very little faith in my mother’s ability to get everyone’s departure times straight. When she’s working on a book, as she was then, she tends to become preoccupied with what’s happening in her story and more than a little foggy about what’s happening in the Real World.

My mother is a writer. Every day—or almost every day—after we’ve all gone to school and my father has left for work, she goes up to her room and writes for five hours. And then, four times a year, she sends a new book off to her publisher.

Two of the four are gothic romances. You know, with heroines who go to live in crumbling old castles where dark family secrets are buried and everyone acts strangely and the heroine finds herself in Terrible Danger. She writes those under the name of Fiona Westphall. The other two books are westerns.

Yes, westerns. With good guys and bad guys and gunfights—the whole bit. She writes those under the name of Luke Mantee. She picked that name in honor of Humphrey Bogart, who played a character named Duke Mantee in some movie.

Back before she was married and of course, before we all were born, my mother was in the movies. No one famous, you understand, just bit parts. Her movie name was Margo Lancaster. (Her real name was Maggie Luskin.) She certainly doesn’t seem much influenced by the whole Hollywood experience. She doesn’t even have a scrapbook, which I think is a shame. She says she never had anything to put in one.

I’ve read a few of her romances. They’re pretty good, although they all seem very much alike. I asked her once wasn’t it monotonous to keep doing practically the same book over and over again?

“Well, it’s kind of a challenge,” she said, “to write one story twenty-seven different ways, so that the reader never recognizes it’s the same book.”

The westerns I can’t read at all. I think they’re boring. Someone must like them though. My mother sells a lot of books. (She says the westerns are pretty much all the same too. But she seems to enjoy doing them.)

“Would you like a ride?” my father asked. “I’m just about ready to go.”

“No thanks, I’ll walk. I don’t know why you have to go this early anyway,” I added. “You could sleep late in the mornings, get up when you pleased—”

“But normal fathers don’t do that,” he teased. “Normal fathers get up at the same time every day, have breakfast with their family, catch the same train to work—”

“Well it’s no use pretending you’re a normal father,” I retorted, “so I don’t know why you bother getting up early.”

“Because I couldn’t sleep through you kids in the morning; why fight it?”

Normal fathers. That’s a laugh. Normal fathers are not, first of all, named Basil. (What was Grandma Hoffman thinking of?) Normal fathers are named Fred or Morris or George or David or Joe—no one’s father is named Basil. And second of all, no one’s father that I know has a laboratory all to himself at a huge corporation, where he’s got no work to do at all but is just expected to fool around.

That’s right, fool around. He doesn’t have to do anything. He goes in when he wants to and comes home when he wants to and no one bothers him. It seems he’s a scientist who was brilliant enough to be sought after by seven different companies who just wanted him to work in their lab (his own lab, really) because he might hit on something terrific which they could make a lot of money on. He also invents things. The company that finally got him pays him an enormous salary.

You wouldn’t know it to look at him. He wears shorts and a Hawaiian print shirt in the summer (the same ones, every year) and gray work pants and a ratty-looking gray sweatshirt in the winter. And sneakers. When company comes he puts on socks. But he is, everyone says, a genius.

Now the question arises, wasn’t I proud of him? And shouldn’t I have been proud of my mother, the famous authors, and my sister, the actress and bowling champion, and my brother, the musician and captain of the debating team?

Of course I was. I thought they were all really amazing people. The thing was, I couldn’t help wishing that a time would come when they would think I was amazing.

2

JUNIOR HIGH SCHOOL is no big deal.

Back in the sixth grade they kept telling us how different things were going to be once we got into Junior High, and how we would be expected to act mature and be responsible and self-disciplined, but so far the only thing they were right about was when they told us there would be a lot more work.

The teachers keep saying we’re supposed to act like young adults but they keep treating us as if we were still in sixth grade. We move around from class to class instead of staying in one teacher’s room for most of the day, but then, in elementary school we went to different teachers for things like Art and Music and Gym and Library. The only big difference is that in Junior High you have hardly any time between classes, because they allow three minutes to get from one class to the next, and unless you have roller skates and a perfectly clear hallway, it is physically impossible to make it from one end of that building to the other in three minutes. And you couldn’t roller-skate up two flights of stairs, anyway.

This particular day I was sitting in French class waiting for the teacher to arrive. The bell had rung already, and he was late. (I guess he forgot his roller skates.) It was the last class of the day and by the time I got to it I was pretty well up to here with school and feeling more like a caged panther than an enthusiastic learner.

As I sat there wishing for a bomb scare so they would have to clear us out of the school in no time flat and send us home, Beth Traub leaned over and asked, “Are you going to join the dramatics club?”

Beth was also in my English class, but I hardly knew her. We hadn’t gone to the same elementary school. There are four elementary schools in our district but we all go to one junior high, which means that I didn’t know about three-fourths of the kids in the seventh grade.

“Yeah, I guess I will.” By this time the thought of staying in school an extra forty-five minutes, even for a club, didn’t thrill me, but I had announced to everyone that morning that I was going to, so I felt sort of trapped.

“I am too,” said Beth. “I’ll meet you after homeroom, okay?”

“Okay. What room are you in?”

“108. What room are you in?”

“114.”

“Wait for me, will you?”

“Sure.”

Our teacher hurried into the classroom, panting slightly.

“Bonjour, mes élèves.”

“Bonjour, Monsieur Krupkin.”

“Ouvrez vos livres à la page quatorze, s’il vous plaît.”

He wrote “p. 14” on the board, because we were just beginning to learn numbers and hadn’t gotten past dix (10) yet. Mr. Krupkin tried to speak only French in class and sometimes it got kind of confusing. After all, how much French could we understand after three weeks?

The period dragged by. We took turns reading aloud the parts of Pierre and Juliette, who go to école supérieure every day, where they étudient such subjects as la géographie, l’histoire, l’anglais, etc. After école they come home and have a glass of lait and some petits gâ

teaux. Then they do their devoirs. On Sundays they go for walks dans le parc.

It sounded like a very dull life.

I waited for Beth outside my homeroom. She got there a couple of minutes after the dismissal bell, staggering under a load of books, an instrument case and a gym suit half-stuffed in a brown lunch bag.

“They ought to give us wheelbarrows,” she grumbled, “along with lockers. I don’t know how they expect us to carry all this stuff.”

“Do you think they even care?”

“No. No, of course they don’t care.”

There were about thirty kids in Mr. Kane’s room when we got there. Twenty-eight of them were girls.

Mr. Kane surveyed the group and smiled.

“Welcome to the Hillside Junior High School Drama Club,” he said. “I’m delighted to see so many budding young thespians with us. I’m sure we’re all going to have a lot of fun in this club as we learn some of the rudiments of acting. For those of you who are new to the club I want to tell you that we put on two plays a year so you’ll have a good opportunity to develop your talent in front of live audiences. What I thought we’d do today is a little improvisational pantomime. Pantomime is acting without words; you use movement and action to convey what you’re doing or feeling to the audience. We’ll do simple, everyday things you’ve done all your lives, but you’ll use no props, no words, just your imagination. Who wants to start?”

There was some foot shuffling and a few nervous titters, but no one volunteered. We certainly were a shy group, considering that we should have been eager to get up in front of an audience and act our hearts out.

Finally Mr. Kane said, “Why don’t we have one of our old members start off, so you’ll have an idea of what I’m talking about? Jean, would you? And let’s introduce ourselves as we perform.”

A plump, very pretty girl with light brown hair walked to the front of the room. She didn’t look nervous at all. She looked perfectly at ease in front of twenty-nine pairs of eyes.

“I’m Jean Freeman,” she announced.

“Jean played the lead in Sweet Sixteen last year,” Mr. Kane said. “Jean, why don’t you do brushing your teeth?”

And This Is Laura

And This Is Laura To All My Fans, With Love, From Sylvie

To All My Fans, With Love, From Sylvie